About this episode

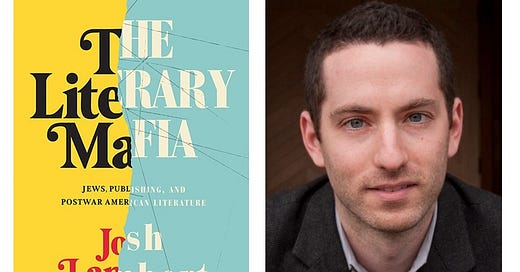

In this episode of "The Book I Had to Write" podcast, Paul interviews Josh Lambert, author of The Literary Mafia: Jews, Publishing, and Postwar American Literature. Josh shares the story of how the term 'Jewish literary mafia' came about in the 1950s and 1960s. They delve into the problems of gatekeeping and publishing's lack of diversity, and ask whether a 'literary mafia' could point to ways to make the industry more inclusive.

Discussed on this episode

Editor Gordon Lish, most famous for cutting Raymond Carver's stories, but who was instrumental in championing Jewish writers like Cynthia Ozick

The concept of the Jewish literary mafia, the evolution of literary representation, and the importance of diversity.

The experiences of Jewish women writers in the 20th century publishing industry

The phenomenon of "whisper novels" as a way for women to address their experiences in the publishing industry

Exploring tokenism and lack of diversity in the publishing industry

Buy the Book

The Literary Mafia: Jews, Publishing, and Postwar American Literature is available from Bookshop | IndieBound | Barnes & Noble | Amazon

Further Reading

What I Saw at the Fair by Ann Birstein

The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe

"I Started the (Shitty) Men in Media List" by Moira Donegan (The Cut)

About the #WhatPublishingPaidMe Campaign by Roxane Gay

Portnoy's Complaint by Philip Roth

Credits

This episode was produced by Chérie Newman at Magpie Audio Productions. The theme music is "The Stone Mansion" by BlueDot Productions.

Show Transcript

INTRO (PAUL): Welcome to "The Book I Had to Write." This is the podcast where I talk to authors about their most compelling stories and why these journeys matter to anyone who wants to publish. I'm Paul Zakrzewski. I'm a professional book coach, podcaster, and essayist. These days with anti-Semitism and white nationalism on the rise, you might wonder who would write a book on something like the "Jewish Literary Mafia". Well, that would be Josh Lambert. Josh was born and raised in Toronto, Canada. He's currently an associate professor at Wellesley College, and he's the author of a new book, "The Literary Mafia," Jews Publishing, and Post-War American Literature. It turns out you can't tell the story of American publishing without exploring its Jewish roots, and without describing some pretty remarkable people and events.

But Josh doesn't stop there. He turns this whole concept of a literary mafia on its head, and he uses it to ask some great questions about the nature of literary representation, about gatekeeping, questions like, what happens to publishing when editors pretend they don't have biases? Or why does publishing continue to be so white, especially since problems with diversity have been coming up since at least the 1970s? And maybe most fascinating, could the so-called Jewish literary mafia actually point to ways we could make publishing more diverse?

If you're interested in the state of publishing today or you just care about books and writers, I think you'll find today's interview really fascinating. A final note, this episode marked the first time since before the pandemic we could record in person, in a studio. We had a blast. A huge shout out to the folks at the PDX Podcast Garage in Boston for hosting us. Now, onto the show.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Well, welcome, Josh. It's great to have you on the show.

JOSH LAMBERT: Thanks so much, Paul. It's great to do this. I really appreciate it.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: So have we gotten approval from the Jewish literary mafia to do this?

JOSH LAMBERT: I mean, the amazing thing is, I'm waiting for people to get upset and, you know, there have been like little stirrings, but so far, like no one has really, really called me with like a complaint or gotten upset with me.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: What kind of stirrings?

JOSH LAMBERT: There's just that sense, you know, this book, you know, it's an academic book and more than I've ever done in the past. I like had a lawyer go over it. I had to like be careful about what I was saying about people because I'm making clear that some people did some things that are maybe like ethically suspect. And, you know, in terms of stirrings, just... I mean, and the main thing and this is funny and like a little bit silly, but there was a review in "The Wall Street Journal," I don't know if you saw, but the most interesting thing to me is that Cynthia Ozick wrote in to contest something that was quoted in the book about like her relationship with Lionel Trilling. And it's just amazing to me that Cynthia Ozick hasn't read the book yet, and she doesn't know that there's a whole bunch of other stuff in the book that she's gonna be even more upset about. So there's just that sense that like, as people get to the book, like maybe they're gonna get angry.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: She must have a Google alert or something. That's really funny.

JOSH LAMBERT: Well, or she reads "The Wall Street Journal," which seems possible.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Good point. Well, we're gonna actually talk about Cynthia Ozick in a bit. But first, what is this punitive Jewish literary mafia? You know, what is it? Who came up with this idea?

JOSH LAMBERT: I start the book by talking about like, people who said those words, right? Like I quote Jack Kerouac, who apparently talked about it. Truman Capote talked about it a whole lot. I quote other people who...you know, this Jewish novelist, Meyer Levin took out an ad in "The New York Times" to like complain about it, which is amazing. But, of course, like what the book really says is that there isn't like something that we can really think of as like an actual literary mafia, but I'm interested in like why people felt that way, like what people were concerned about, what they were scared of.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Yeah, and definitely it seemed like it had its moment, I guess, in the '50s and '60s, you mentioned folks like Capote and Kerouac who I knew had been very anti-Semitic. That was kind of wild to me. What was interesting to me is how you kind of chart that, that that wasn't always the case, that there was this movement from the margins to the center. Can you talk a bit about that, and especially this really interesting term you have about enfranchisement?

JOSH LAMBERT: Yeah. So, I mean, in the briefest way, there's change over time that at the end of the 19th century, you can look around and you can find a couple of Jewish people who like maybe had editorial roles in one place or another, but what you find much more is a really pervasive sense that anti-Semitic discrimination was just expected throughout like the literary world. That if you were a Jewish person and you came to a publishing house, if you came to an English professor, if you, like, wrote for a magazine, someone would sneer at you, would say like, that's not for you. You know, there's enough stories that I collected of people who wanted to get a Ph.D. in English and were turned away and said like, "You're never gonna get a job. It's not a thing for a Jewish person to do."

And that was very typical in the 1890s and the 1900s and 1910s. And what I was interested to try to do is attract how that changed because obviously when I went to college, it was very normal for Jewish people to be English professors, to be the editors of magazines, to work in publishing. And it really did change over time and it changed in sort of big chunks. Like you see it with the founding of publishing houses in the 1910s and 1920s. You see it with academia starting at the end of the '30s and into the '40s. You see it at like mass magazines, really not until like really the '50s and even the '60s. So just in different areas of culture and as I think like is probably pretty familiar to people, when there's that kind of discrimination, it's not formal, right? Like no one like posted a sign, "No Jews allowed," at Harper Collins or whatever, but, you know, there was a sense of like what was right or who were the right people and that it took time to change and it really did change over 60 or 70 years.

And when I was thinking about how to describe that change, you know, a lot of the words you end up using are like power or influence. And some of those terms are so freighted with like anti-Semitic connotations and they might not feel that accurate because when you say that a group gains power, it really does seem like they're acting in concert, right? Like it leads to the idea of like a mafia. I found that term enfranchisement like interesting because when we think of people getting the right to vote or getting like enfranchised, we don't think like, "Oh, they're all gonna vote the same way or they're all gonna make the same choices." We just think that like, this is this power that's been kept away from them and now they can exercise, like, this opportunity to make decisions.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: And you definitely argue for more complexity in understanding their choices throughout the book. And I should say that the book is structured in this really interesting way which is that you look at very kind of specific cases throughout these different areas of culture. And so I thought we could kind of touch on a few of them and with an eye to kind of some of the broader themes that they expose. So first off, I was really interested in your discussion of Gordon Lish. So first of all, who is Gordon Lish and what's he best known for?

JOSH LAMBERT: Right. So until I started working on this project, what I knew about Gordon Lish was what I think like the trivial pursuit question about Gordon Lish would be about, which is that Gordon Lish was this editor who is most famous for cutting Raymond Carver's stories. That Raymond Carver, who is...if people don't know, I think most people listening probably know him as a short story writer. You know, his stories are taught all the time. It came out in the '90s after people started to look at Lish's papers that the stories that Carver had written were about twice as long and that the versions of them that we all got taught in college were, like, cut down by half by this editor. So like that's what Lish became known for. And he's a bit of like an example case, I think, when you're writing about or talking about like the role of an editor versus the role of a writer and like how that relationship works. The other thing I should say about him, frankly, is that he's also super well known as like a teacher and mentor that a lot of the people who teach at MFA programs studied with him, he led these very strange eccentric sort of writing seminars that people talk about.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: He had a nickname, right?

JOSH LAMBERT: Oh, well, I mean, he called himself. I mean, this was like the kind of nickname that he like was such a self promoter that I think mostly just came from himself that he would sign his memos, which I've seen in like Captain Fiction.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Oh, I didn't realize, I thought people ascribe that to him.

JOSH LAMBERT: I mean, maybe it started with someone else, but like he absolutely took that kind of stuff on himself. I mean, he was amazing. I mean, he's still alive. He is a sort of brilliant, hilarious writer. He could charm someone in a letter. I mean, famously, he got the job as fiction editor at "Esquire Magazine" almost out of nowhere on the basis of just this unbelievable letter he wrote to the editors and said, "I should be your fiction editor."

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: And you spent time in the archives. And I want to talk to you more about the research in the book, but you spend time in his archives, right? To...

JOSH LAMBERT: Yeah, yeah, yeah. His papers are at Indiana University in Bloomington. And, you know, they're amazing. And you can see, and what I love most, I don't talk about in the book is he would regularly write a memo at Esquire exhorting people to come out for like the company softball team. And they were just like these, like, unbelievably bombastic like interoffice memos telling people like, "We're gonna crush the other teams." And, you know, I can't even do justice to like how electrifying and intense his memos were.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: And the other thing we should say about him is that he's very Jewishly identified and you spend time really kind of tracking that. And so if there were such a thing as a Jewish literary mafia, you would expect someone in that position to champion the kind of stars of Jewish...the Jewish literary firmament, you know, the Malamuds and the Bellows and the Philip Roths. But instead, what's interesting about him is that he actually discovered or championed early other people, especially two women that you talk about, Grace Paley and Cynthia Ozick, and this is his relationship with Cynthia Ozick that I'm interested in. Can you talk about that relationship?

JOSH LAMBERT: Absolutely. No, this was amazing to find. So, you know, as you say, one of the reasons I got interested in Lish is he's one of the few editors I could find who really talked extensively about wanting to support Jewish writers, like being a Jewish person and saying, "That makes me interested in these other kinds of writers." A lot of editors, even if they do that, they feel uncomfortable with admitting it. And I found it like, you know, really compelling that he was willing to do that. One of the best examples of a writer that he worked with, I mean, it's really...their relationship is incredible, and I think is a powerful story in and of itself. And what's wonderful about it is as much as they like may have met in person at times, they wrote these incredible letters back and forth.

So like we can sort of watch their relationship develop. And it really is the case that Cynthia Ozick, if people haven't read her, is an incredible writer. She won more O. Henry Short Story prizes than any other writer ever has. I think four first prizes in the O. Henry contest. She writes criticism for "The New Yorker" all the time. She's written, you know, dozens of books. David Foster Wallace once said she was one of his favorite writers. Like she's an incredible pro stylist, a fascinating critic, a complicated thinker. And when she first connected with Lish, it was right after he got to Esquire to be the fiction editor. And somehow I think she just submitted stories or her agents submitted stories, but they got to sort of communicating through letters. And what's incredible to see in her letters is she knows that her interests are pretty particular and niche, and she's fascinated with like the history of Jewish writing and of Hebrew writers and Yiddish writers.

And she writes these stories that are like really intensely wrapped up in like Jewish textual history, stuff that like is obscure even to me and I'm like a professional Jewish studies scholar. And she sent it to him and sometimes with a note saying like, "I know you're never gonna publish this in Esquire. It's ridiculous." And then he would turn around and find a way to get it into the magazine. And that really helped like launch her into the career she's had where, you know, it's just normal to see her in "The New Yorker." It's normal to see her in the most prominent sort of places in American Letters, even though sometimes her work really is like just very particular in its own way, like in its interests.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: You have this line here that the thing that unites these different writers that folks may not realize that Gordon Lish championed is that they had, I think you wrote sinuous and beguiling and surprising sentences. And the connotation there is that they're multilingual, some of these writers like Paley and Ozick, there's kind of Yiddish or immigrant cadences. But what's also interesting about Lish is when you went to the archives, you discovered that despite this kind of eclectic stable writers that he championed, there's almost no African American writers that you could find or Asian American writers. So can you talk a bit about that irony in his career?

JOSH LAMBERT: I came to even ask that question relatively late in thinking about it, right? Because the thing that I had found with Lish is that he was interested in supporting other Jewish writers. And you think to yourself like, "Well, that's normal," and like there's no reason to criticize any editor for being interested in what they're interested in. But at the same time, I wanted to ask the question of like, okay, so what wasn't he doing or what did that mean he might not have been paying attention to? And I should say I'm not the only person to be thinking about this in terms of Lish, I'll really recommend, I don't know if you've read it, Jess Rowe has a book called "White Flights" that has a chapter that sort of takes this up. And because I wanted to be careful in the book, I really wanted to like look and check.

And the thing one should say is that it's not that Lish wasn't interested at all. I can like point to a few cases in which he published Amiri Baraka in like the little magazine he edited in Palo Alto, like, early in his career. But you can make a long, long, long list of like writers associated with Lish who see him as their mentor and as the most important figure in their literary career. And it is really, really hard to find more than one or two or three writers of color whoever, you know, had that relationship with him. And again, I'm not sure what exactly we should say about that, right? It's not that every editor needs to do everything, but particularly if you read a lot of American literature and you have that feeling for the way in which different kinds of immigrant writers, different writers from minority communities, what they bring is a kind of pressure on the language that like makes English more interesting. And that seems to be what Lish is most interested in. It feels a little strange that he wasn't more involved with writers from other backgrounds.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: You also look at the case of Jewish women in publishing and if there had been such a thing as a Jewish literary mafia, one would assume that would've positively impacted Jewish women writers in the 20th century. But in fact, you look at, I guess, three different writers specifically, Ann Birstein, Rona Jaffe, and Trudy Gertler, who I had not heard of. What is it that you actually discovered by kind of exploring novels and writing by the three of them?

JOSH LAMBERT: Yeah, but all three of them wrote novels that like talk about the publishing industry or pulled back the curtain on how editor relationships work. And I was interested in looking for the ways in which being Jewish might have helped them, might have connected them to other people, might have given them opportunities because that's, you know, what the book is about. And I think that it's certainly the case, right? Again, there's no organized literary mafia, but Ann Birstein is this fascinating writer who published a novel very young, like in her early 20s, and then married Alfred Kazin, who's one of the leading literary critics in the country at the time in the '50s. And through him, she goes to all the parties and she meets all the people and she gets a real opportunity to connect with all sorts of people who were the most powerful editors and writers around.

What she finds is that they're not that interested in her, they don't take her seriously. The sense I get of Birstein is that she was incredibly confident, like a very attractive, self-possessed woman, and they sort of saw her as like somebody's wife and they didn't like really want to care about the writing she did, even though in this group, like the thing she did, writing novels, was the thing that they prized more than anything. Like the most important thing in the world you could do was write novels. And in her memoir which is called "What I Saw at the Fair," she talks about like he'd have a visiting faculty gig at Amherst or something and there'd be this big conference on novel writing and all these writers would come in, and Saul Bellow would come in and, you know, Ralph Ellison would come in and they'd talk about the novel and like she'd be like serving the drinks.

No one would like pay attention to her or even ask her a question, even though she had at that point, you know, published five or six novels. You know, there's that sense that in those years in the '50s, '60s, '70s, the overall sense I got was that there were these opportunities for women, like sort of new opportunities to play roles in the publishing industry to, you know, have more opportunities to publish, but they were really complicated by like all the different ways that misogyny impacted their lives so that, you know, those opportunities were there, but an editor might act inappropriately with them or expect something outside of a purely editorial relationship.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: You referenced this kind of famous or infamous moment in Me Too, the Shitty Men in Media, the Google list that seems to have gotten Moira Donegan into a lot of trouble. And you come up with this really fascinating term of whisper novels, that in 2018, as a kind of counterpoint to women finding a way to talk about what they were actually experiencing. Can you talk a bit about what these whisper novels were?

JOSH LAMBERT: Yeah. What interested me, to take an example that's like easier to talk about because all the people are dead is...

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: And we won't get sued.

JOSH LAMBERT: Right, exactly. I think we're safe is Rona Jaffe's novel, "The Best of Everything" which was a big bestseller in the '50s and is a kind of light fairly poppy novel. I mean, I don't wanna undervalue it, like, it's an excellent novel in its way, but about young women, you know, who moved to New York to work in the publishing industry. And what I found in rereading it, you know, for this project, I had read it a while before, I didn't remember it that well, was that it's incredibly precise about the way that the young women at this publishing company, which is based on where Rona Jaffe actually worked, are sexually harassed by one of the senior editors. It just like over the course of 300 pages shows you what he does and he's more or less shown to be a lecherous, old fool.

And the novel sort of takes him on a journey from being this authoritative like scary presence in the office to like a totally decrepit and disgusting old man. But there's so much precision in that portrait of like what an editor might do in calling you into his office, and how he might act, and what he might say and what he might ask you to do. You know, it's not that I'm saying that that happened particularly to Rona Jaffe, but I know that that book was built out of her own experiences and the experiences of about 50 women that she interviewed and talked to. And we know that that character was based on a specific person, right? Not just a general composite of editors who existed, but based on an editor named William Lengel who worked at Gold Medal Books at Fawcett where Rona Jaffe worked.

And the question that becomes interesting to me is really what we do with those kinds of fictional portraits that are very easy to align with a real person and that show that person acting unethically or criminally. Obviously, like, you can't use her novel, which is fully fictional and there's no question that it's a fiction as testimony against him or as like evidence in a court. But I think that when you understand like the kinds of things that happen to women who complain about men's abusive practices, you can understand why a woman might want to use fiction as a kind of shield to spread that information to like let other people know without taking on all the sort of risk or vulnerability of like an actual legal proceeding. And so in a way, I see those novels working like whisper networks, which I think is how in the contemporary world how this works.

I mean, in the fields that I'm in, I'm vaguely aware of, I don't think I'm like at the center of those whisper networks, but like you hear, "Oh, this person over here might be a person to be avoided or, you know, something might not be right over here." And I think it's just a completely fascinating thing to do that same thing in a novel that sells hundreds of thousands of copies and that like gets made into a movie and is talked about in all the newspapers. And somehow, strangely, like in all the reviews I read and all the academic criticism that I read, no one sort of pays attention to that. And maybe that's right in the sense because it's meant to be noticed by the people who are supposed to notice it and not, you know, make a bigger deal of it.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: So I kind of wanna draw out some of the other big implications in your book. You have this fascinating...I think it's in a footnote, but you talk about an interview that you did with "The New Yorker" fiction editor, Deborah Treisman. Can you tell me the story, like what it was that you asked her and what her response was?

JOSH LAMBERT: Sure, yeah. This was for a while ago, I think like in about 2012, 2013, I was interested in the fact that "The New Yorker" had really published a lot of post-Soviet Jewish writers: Gary Shteyngart, David Bezmozgis, many, many others. And it occurred to me like David Remnick, who edits the magazine, came up as a journalistic specialist in Russia and is a Jewish guy himself. And Deborah Treisman is of partly Jewish descent. And I thought to myself like, is there any self-consciousness about the fact that we are in part Jewish people or Jewish-descended people, however they might wanna describe themselves and we're publishing all these Jewish writers?

And, you know, unsurprisingly, and very reasonably, like, her response to that question, which was very generous to give me a response was, "No, of course not. We're interested in the very best fiction." You know, I don't have the quote in front of me, but, you know, we're not interested in what backgrounds people came from. We want to just publish the very best work that we can.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: What did her kind of gain saying tell you? How did you read that?

JOSH LAMBERT: To me, it's just a good example of what like most editors will tell you and most prize judges will tell you, like if you ask people who judge a big literary prize, what they'll say is, "Oh, we just wanted to pick the best book." There's lots of theory that supports this, but like, also if you just stop and think about it for a second, it's pretty clear there's no such thing as the best book, there is no best, right? There's no objectivity in the field of like novel writing. Some people like some things better, other people like other things better. And what people think of as important pathbreaking pioneering crucial will depend so much on who they are and where they come from and what their experiences have been. So I don't think it's wrong that an editor says, "No, no, no, I just picked the best thing." But I think it's a little bit...

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Disingenuous,

JOSH LAMBERT: Maybe disingenuous, maybe in a sense just a dodge. And I think the thing that we like struggle with, that everybody who works in culture struggles with is to articulate as clearly as possible why they make the choices they make, right? To actually get an editor to say why they chose this book or this writer or this subject over this other thing is incredibly complicated because mostly it comes down to like, it's how I was feeling that morning or my partner really liked it or, you know, I was talking about it with these friends and it seemed really interesting, so I thought it would be worth going ahead with it. And none of that seems like objective enough or formal enough to justify the huge amounts of money that are spent in book publishing and in other cultural industries. So I think that that language of like, 'Oh, well, we just picked the very best thing," is kind of a cover for all of that stuff that goes underneath. And that's what I wanted to write about in the book.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Kind of unconscious biases.

JOSH LAMBERT: Yeah, unconscious, but maybe even conscious in a sense, conscious but unpleasant to talk about, right? You know, if you are an editor, a major editor and you just say like, "I like dogs but not cats," if there's ever a book with a cat in it, I'm gonna throw it in the garbage, but if there's a dog, I'm gonna take it, like, that would seem very silly, but like those kinds of biases just exist in all people and there's nothing like wrong with that. There's nothing reprehensible about liking cats or dogs better than one or the other. I don't like either. But like the problem isn't that that exists, it's that it feels so difficult to talk about or be transparent about.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: And one of the implications of it, I think, and you raised this in your book, is that it perhaps has led to a huge problem in publishing, which is not the fact that there's a Jewish literary mafia, but that it's an overwhelmingly white institution. And it's a problem that publishing has known about for a long time and has kind of made noises at different points about changing. And yet you cite all the stats that, you know, we've all heard about the incredible small percentage of people of color working in publishing.

I was also thinking just apart from editorial stuff, just writers, there was the whole Twitter thing that happened in 2020 with Roxane Gay, you know, and the #publishingpaidme to talk about the real disparate nature of advances that writers of color get. Can you talk a bit about this idea of tokenism, and what publishing has done, and maybe what the example of Jews in publishing could tell us about other options?

JOSH LAMBERT: Yeah. So, look, I'm not by any means the only person thinking about this question of like, what do you do about diversity in publishing? And what strikes me with force about it is that people have been talking about it since at least the '90s in exactly the same terms and people keep trying to change it and it doesn't seem to change. And I think that I'm really moved by reading the accounts of people of color who have worked in publishing, how much they align with like the classic description of tokenism, right? Which is that if you go back to the person who we think of as coining tokenism is this sociologist named Rosabeth Kanter. And if you go back to the way she talks about it, she says like sometimes the token gets like advantages from their status, right?

Because they're the only one and, you know, people are excited by working with them or knowing about them, but at the same time, they have all these disadvantages that typically outweigh those advantages. And just to make the connection to what we were talking about earlier, so I think there's been a lot of that tokenism. And the other thing I think there's been a lot of in publishing is a sense of that meritocracy that, you know, we're not gonna think about people's backgrounds. That won't help. We'll just think about who's the best, who's graduated from the best program, or who's got the best credentials?

And I think that from my perspective studying the history of Jews, this minority group who really were able to succeed in this field, the thing that we can take away is that it's quite possible for an ethnic group or a minority group to get benefits from their membership in that group. And usually, like, those claims to objectivity are about denying that anyone should get benefits from their identity status, right? And it's reasonable because we don't want the people who already have power to get more power from their identity status. But if we deny minorities the opportunity to get benefit from their status, like, what we see in the book is there were many, many, many cases, not of a mafia, but of a Jewish person who did a favor for another Jewish person or helped someone out or who was interested in their work.

And that helped Jewish people to sort of succeed. And, of course, if you wanna see minority groups who have been like denied opportunities, if you wanna see them succeeding, they need that. Like it needs to be the case that an African American person in publishing feels totally comfortable saying. And like Roxane Gay, I think, is a pretty good example. Like I'm gonna support other people of color. Like that's what I wanna do. I wanna support other writers who are expressing things similar to what I've expressed. But I think the problem is if the industry says, "No, no, no, we need people to be objective, we need people to be meritocratic, and there's something wrong with people helping other people out just because they're from the same group."

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: And so your conclusion is what we actually need are more literary mafias, meaning more groups that are getting the same kind of access and power?

JOSH LAMBERT: I think so. I think like we would live in a much better, healthier like cultural environment if we felt like, "Oh my God, publishing is being taken over by..." name your small minority group. Like even if it's like a very small group because by the way, Jews are like a tiny group and it was no problem, it did not like destroy American literature that they had influence or like succeeded in it. So like I could even imagine if Vietnamese Americans became the most prominent editors in the country of every like magazine you can think of, I think that would be great. It would be really cool. Like just imagine a world in which the editor of "The Atlantic" and of "The New Yorker" and the top editor at Random House and the top editor at every other press you can think of, at Simon & Schuster and Penguin, was Vietnamese American? Like, that would seem very strange and it would seem like something maybe weird had happened, but I think it would like only make for a more interesting, like, vibrant, and like compelling literary environment.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: And if there was a book the Vietnamese literary mafia, I guess that would speak to the fact that they had actually really succeeded.

JOSH LAMBERT: Well, right. A lot of people would complain about it, but I think like that would be the sign that it was actually working, that something was happening.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Can you talk to me about how this book came to be?

JOSH LAMBERT: Yeah. For me, you know, there's a few different like origin points for the book, but really being an academic and like writing a book over a long period of time and like you could say maybe like 10 years is how long I worked on this book. In a way, it reflects a lot of just what was happening in my life. But even before I started to work on this book, I was like serving as a prize judge and I was doing a lot of book reviewing and I was like connecting with a lot of people and a lot of the kinds of questions that come up in the book and in the book get answered historically were just like happening in my life. I was like having to make choices of do I know this person too well to review their book?

Do I know this person too well to like advocate for them to get a prize? Does this person like me enough to like help me out and like give me an opportunity? And I think like almost anybody who's like working in any kind of cultural field will like have those experiences constantly all the time. Like I imagine you do. I don't know.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Of course.

JOSH LAMBERT: Yeah. Like, so you're always thinking about those questions of what are the ethics of the decisions I'm making? And like how do I even make those decisions about who do I owe something to, and who do I not owe something to? And for me, you know, thinking through all those questions and then on a few different projects I was working on, I started to see those popping up historically.

Like one of the earliest pieces of the book that we didn't talk about is Lionel Trilling who was this like incredibly influential teacher. And I happened to stumble across like what he would do for his students. I mean, he could send a letter and a student would get a book deal with like Farrar, Straus or whatever, and it was an incredible thing that he could do. And I was interested in if you had that kind of power, how would you make those choices of who you help or, you know, who you don't? And I think, you know, in part, these were also the years, I'll say, like, when I was like having kids, when my dad was getting sick and dying, and I was thinking about those questions of like nepotism and like what we get from our parents or for the people who come before us, and also like what our responsibilities are or how we feel about sort of helping our kids versus helping other people.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: For listeners who might not be that familiar with the process of publishing an academic book as opposed to a trade book, can you describe what the process of getting this book through the editorial process has been like, the publication process?

JOSH LAMBERT: Sure, yeah. So, I mean, often, your first academic book will be like based on a dissertation that you wrote. And this is my second book. So this came together, you know, over a few different years. I was interested, you know, pieces of it started to fall into place, and I started to publish a couple of pieces in journals that were, you know, related in one way or another. And I knew I was gonna start looking for a publisher soon, and I published a short piece based on some of the research and I actually heard from an editor in Academic Press who said, "Oh, do you wanna meet at one of our conferences?"

And I went to meet with her, and basically, the way that it worked for this and often for second books in academia is I did a sort of proposal that described the argument of the book with a couple of chapters, and that went out to peer review which was anonymous people out in the field, people who study some of the same things that I study who read it over and gave feedback and decided whether it seemed like the kind of project that the press should do.

And at that point, I got a contract and finished it. And then after I finished the whole manuscript, it went back out to another peer reviewer and they sort of decided that it was worth going forward with. And then, yeah, and then it went into production, you know, pretty normally for how, you know, a trade book would go into production.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: This just occurred to me, but does academic publishing kind of fall under some of the same issues that you describe in the world of New York publishing?

JOSH LAMBERT: Oh my God, of course. What was amazing is when I sat down, like, the very first time with an editor to describe the project, very quickly, she stopped talking about my book and started telling me stories about like her experiences at the press, and like the people at the press who were married to each other, and the person who helped out their kid and, you know, all those sort of stories because of course, it happens absolutely everywhere. And because of the peer review system, in a way, it's almost explicit and formalized that like other people in the field have to support me for my work to go forward.

So like every time I'm like nice to a person at a conference, I'm thinking like, "Oh, maybe that person is later gonna have to review my manuscript." So there's all those sort of like personal and network issues. Yeah, absolutely. I see it all the time. Once you start to look for it, you see it pretty much everywhere.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: What was your experience of doing this book compared to your last one? And what did you learn from doing your first book that made this one easier or more difficult or different?

JOSH LAMBERT: Interesting. I think like the privilege of being in academia is that I could do so much of what I did the first time the second time. Like there wasn't that much pressure on me to move quickly or to sort of have to get it done. And, yeah, what I think I took from the first book was, and what I like to do for better or worse is just like dive in as deep as possible to a topic and spend as much time as I can getting archival research done, finding things that other people haven't found, finding like spots of the story that haven't been covered.

And again, you know, I don't know how it'll work for readers, but I think that what I've found as like the practice that makes sense to me is like my books, if I would say one thing about them, they have like attractive titles, they have like a sort of framing that hopefully gets people in the door and then are actually pretty rigorous and serious works of academic scholarship inside of that.

So I know that can be like a little bit off-putting and I worry a little bit as a book comes out into the world of like, oh, some people are gonna read this and feel like, "Oh, no, this isn't the sort of fun gossipy book that I expected it to be." I think there's some of that element in it, but I think finding that balance has been like the thing that I'm trying to do as a writer.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: I guess this would be the time to point out, although this is a podcast and people will be listening, yours has one of the most fun book jackets that I can think of. Explain the book jacket and kind of the reference.

JOSH LAMBERT: Yeah. So this, I can't take credit for because it wasn't really my idea, but this designer did just a really wonderful job. The cover is like split vertically down the front and it's as if the left side has very much the color and styling of the jacket, the sort of iconic jacket of Philip Roth's "Portnoy's Complaint," and then it's as if it's been ripped down the middle and on the right side, it's kind of a paler, and blue, and with like some lines crisscrossing as if to say like, "This is the story underneath the story of the literature of that era." And I think it's beautifully done. Like the moment I saw it, I loved it and I was so grateful. So, yeah, it's always amazing when a designer sort of gets what you're thinking about.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Yeah, it's pretty great. You're a scholar of Jewish American literature and a cultural historian and I know that you...I was reading in your biography, I mean, you go looking for areas that are kind of understudied. How do you feel like you come up with these?

JOSH LAMBERT: There are a lot of different ways to think about what you're supposed to do as a humanities researcher, but I think when I talk to students or when I like say what my job is, it really is to like find something that interests me, to read everything that people have written about it and like, really everything. Like go to libraries, go to wherever and just like read...you know, if it's a book or a writer, read everything they wrote, read everything that was written about them, that's ever been written about them, and then try to decide for myself, is there something like that hasn't been said yet that's interesting to me?

Usually, I find that there is, but that's why like I don't find myself writing about Shakespeare, right? Like, it's a lot harder to find something like brand new to say about a really major figure. But what I try to do in the book is like find a figure who I think is really compelling in one way or another and has something to offer or has a sort of story that's meaningful, and then see what everybody said and see what they haven't said yet.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: Well, Josh, I want to thank you so much for your time. This has been a great conversation and really fun.

JOSH LAMBERT: Thank you so much, Paul. It's so much fun to talk about this book, and really like I'll say with...especially with people who I've known for years and who I'm constantly thinking about how we know each other and how kind it is for you to like do this for me, it sort of really is appropriate for this book.

PAUL ZAKRZEWSKI: I know, I wasn't gonna say. You've been listening to my interview with scholar and writer, Josh Lambert. I'm Paul Zakrzewski. If you enjoyed the show, then I hope you'll subscribe to it. I'm always grateful for reviews and for sharing the show with friends. To read a full transcript of this and every episode, sign up at thebookihadtowrite.com/subscribe. And if you're working on your own book you have to write or you wanna get started, maybe I can help. I love supporting experienced authors with expert advice and focus coaching. I help writers craft book drafts, agent pitches, book proposals, and more. Find out more about me and my coaching at thebookihadtowrite.com/coaching. That's thebookihadtowrite.com/coaching. And thanks again for listening.

Share this post