Here’s a guest post from journalist and author

, originally published on her Substack.A few weeks ago, The Guardian ran a jaw-dropping feature story to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide. In it, victims and perpetrators are interviewed side-by-side as they discuss how they carried on, and in these particular cases, found peace and forgiveness.

One story in particular, told by a 70-year old woman named Liberatha Nyirasangwe, continues to haunt me:

I saw the men coming and fled. Inside the house they found my three-month-old twins and killed them. They slaughtered all my family. Afterwards I went insane. I walked outside naked, cursing everyone. My madness lasted for years, until I was asked to join sociotherapy [a type of community therapy.] It helped that the perpetrators told the truth. I saw that they are human beings, too.

While Nyirasangwe’s story is devastating, it was the response by Alphonse Kanyemera, 78, the man who killed her brother as well as a priest, that keeps coming back to me:

The devil must have possessed me. In prison I fell ill and thought they would let me die. But they took me to a hospital where a nurse from my region cared for me like a daughter. Now Liberatha and I take care of each other. We live on the same hill. I hear her when she calls.

I hear her when she calls.

I replay that line over and over again in my head. A victim and a perpetrator. Thirty years ago, one ruined the other’s life. Today they help each other survive. It’s opened the door to a question I’ve had all my life, trying to imagine what it was like for my grandmother to return home after being deported to Auschwitz. What did the villagers, her neighbours feel when they saw a survivor? Did any of them ever speak to each other years later? I want to know, how, after a genocide, do victims and perpetrators continue living? And is it possible that they do it together?

Oppressed-Oppressor Dichotomy

We define ourselves by understanding not only who we are but who we are not. Victim not perpetrator. Oppressed not oppressor. In a culture that eschews binaries, these ones stubbornly hang on.

But what happens when the oppressed become the oppressor? Paulo Freire explored this idea, as did Nelson Mandela, Karl Marx, and the list goes on. Does the victimizer stop being a victim? Or, are they still a victim but on the hierarchy of sympathies, do they fall to the bottom of the barrel? Do they have any rights to sympathy at all?

It’s a difficult question to mull since the devastation on October 7, where the massacre was quickly eclipsed by the ensuing horror in Gaza. Who is to blame? For many, the answer is strictly one or the other. I struggle to have a cohesive conversation with anyone about it, lately. Too many people are hurting, myself included.

Then I discovered an unlikely philosopher through which I can safely explore these issues again:

Magneto.

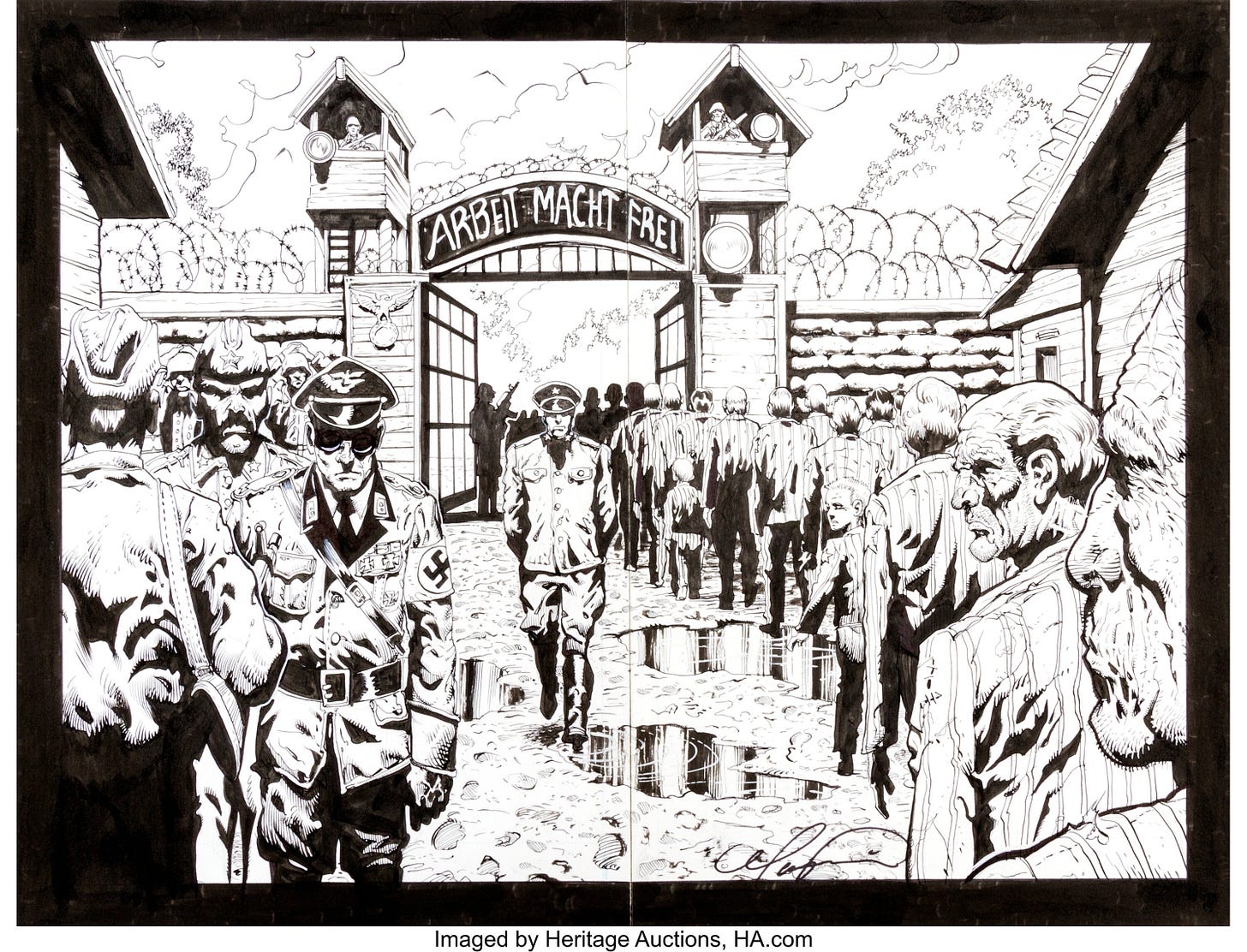

Forgive me, dear readers, for lumping in Magneto with luminaries like Marx, but the X-Men has always tackled difficult themes and this latest series, X-Men ‘97, does not disappoint. For those unfamiliar with the franchise, Magneto was born from the ashes of Auschwitz and the experience taught him that different people cannot live together. Mutants, he often posits, are the superior race, and maintain an ‘us or them’ sensibility. Like many others, he chose his own kind.

Survival as a Superpower

I’ve loved X-Men for as long as I can remember. I dragged my kids to many of the films. (In their defence, they say they enjoyed them, too, but likely not as much as I did.) My favourite characters vary — for years it was Wolverine. But quickly, Magneto’s backstory, and its familiarity, captured my imagination. I understood his pain, and likewise, I understood his desire for revenge.

Born Max Eisenhardt (or in some cases Erik Lehnsherr), his middle-class German Jewish family flees to Poland after Kristallnacht, where they are interned in the Warsaw Ghetto. Max’s family perishes but his superpowers allow him to survive Auschwitz.

He moves to Israel after the war, where he meets his nemesis/best friend, Charles Xavier. Their relationship, more than anything, is the crux of the series. Early on, Magneto warns Charles that humans compete for everything, even victimhood. While haunted by his past, Magneto refuses to allow victimhood to define him and embraces the role of victimizer, believing that like his family, the mutants will one day end up in concentration camps.

For years, many interpreted the Magneto-Xavier relationship as a version of Malcolm X to Martin Luther King, and the analogy certainly works. However, Chris Claremont, an X-Men writer for many years, says Magneto was inspired by former Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Claremont said he always intended for Magneto to take over the X-Men, much like Begin and his right-wing Likud Party took over from Israel’s left-wing founders in the 70s. With that insight, it’s impossible to see the series with any other lens.

In the first few episodes of X-Men ‘97, Magneto is certainly challenging himself to question his previous genocidal beliefs. (He did try to destroy the world in X-Men Apocalypse after he destroyed Auschwitz.)

Early in this series, Magneto explores what capacity he and others have for tolerance. Can people change? Can we live together? As politicians and pundits explore what comes next after the war in Gaza, I can’t help but feel (or rather, hope) we are all reckoning with the same questions.

In fact, Magneto openly mulls the oppressed-oppressor dichotomy while willingly standing trial at the U.N. for crimes against humanity. (Sound familiar?) If the writers of this TV show aren’t psychic, they are at the very least prescient.

Magneto’s character is deliciously complex. He exudes a sense of superiority, not only for his awe-inspiring ability to literally move the earth, but for his status as a survivor. It reminded me of a man named Daniel Chanoch, who was interviewed in an Israeli documentary called Numbered about survivors with Auschwitz tattoos. In contrast to the other survivors, Chanoch spoke about his tattoo with glee and said it makes him “superior.” “I owe my birth to my mother’s womb, but I owe my life only to myself, sweetie,” he tells the interviewer.

I didn’t see that audacity among the survivors I grew up with, but I understand its logic. Magneto, too, has an Auschwitz tattoo and like Chanoch wears it proudly. It’s not only his origin story. It’s a superpower.

Trauma to Terrorism to Trauma

Magneto’s character uses his history of trauma to explain and in some cases justify his extreme tactics, even terrorism. The creators of X-Men don’t shy away from constantly giving him reason to distrust and seek revenge. This new series even has its own Dr. Mengele for X-Men, one that believes the original Mengele didn’t go far enough.

In our current war (and war of words), which consistently returns to Holocaust analogies to justify and describe atrocities, Magneto is truly an anti-hero for our era. Yes, he is a terrorist who has been terrorized, but through him we see the actions of others mirrored, and they too are victim-victimizers. Scott Summers, or Cyclops, announces in the first episode that they are the good guys. But really, there are no good guys.

That doesn’t mean the flawed heroes don’t mull very difficult questions. In this case, can you be good and be safe? Can you trust people who previously harmed you? Is there a way for different people to live together?

I’ll add my own questions: Will Israel’s increasing isolation undercut Holocaust memory? Will the oppressed/oppressor dichotomy cancel each other out? These are all themes I am aiming to uncover in The Bubbe Tapes.

How do we move forward? Can Rwanda be a model? Can the X-Men? What capacity do we have for tolerance?

“I am trying to be better,” Magneto says, when asked about moving past his criminal ways and paving a new future of co-existence.

So am I, I think. So should we all.

Thank you, Paul!