How Do You Craft a Compelling Child Narrator?

Orwell, Cunningham, and the secret of "double" consciousness in memoir

(An earlier version of this essay appeared on Essay Daily.)

In all the workshops I’ve either attended or led, it’s the narrator of a memoir set in childhood that seems to give writers a particularly tough time.

It may be that childhood memories in particular feel somehow magical, sacred—not to be changed or reshaped—while for newer writers, there’s also the potential for strong or traumatic feelings to suddenly emerge.

Whatever the reason, in the rush to recover sometimes long-neglected memories, I’ve seen even elderly writers lose touch with their adult selves, permitting the voice on the page to collapse into a tedious, child-like reverie that’s not fun for anyone but the author to read.

So I went back to a number of favorite books and essays to better understand the issue and what techniques the newer memoir writer could develop to further strengthen their writing from childhood.

My first stop was Phillip Lopate’s influential essay “Reflection & Retrospection: A Pedagogic Mystery Story.” Here Lopate describes the need for the memoirist to deploy a “double perspective” that allows the reader to “participate in the experience as it was lived, while conveying the sophisticated wisdom of one’s current self.”

That double perspective, or double consciousness is the yeast in memoir, without which your story won’t properly rise:

In any autobiographical narrative…the heart of the matter often shines through those passages where the writer analyzes the meaning of his or her experience. The quality of thinking, the depth of insight, and the willingness to wrest as much understanding as the writer is humanly capable of arriving at— these are guarantees to the reader that a particular author’s sensibility is trustworthy and simpatico.

More than the absence of a psychologically astute narrator, it’s often the limited syntax of many workshop memoirs that could feel tedious. Who wants to spend page after page after page in a manuscript aimed at adults, but who has confined herself solely to the vocabulary and rhythms of a child?

As Lopate himself concludes: “What is important, in writing about childhood, is to convey the psychological outlook you had as a child, not your limited verbal range.” [my emphasis].

As wonderful as Lopate’s observation is, it doesn’t necessarily explain the trick of how to create a narrator who can convey the child’s narrow psychological range, but who’s writing isn’t limited by it.

So I ended up returning to two favorite memoirs—one a brilliant, lengthy (18,000 word!) autobiographical essay about abuses in the British private school system; the other a witty and compulsively readable memoir set in the Jewish milieu of the 1940s Bronx.

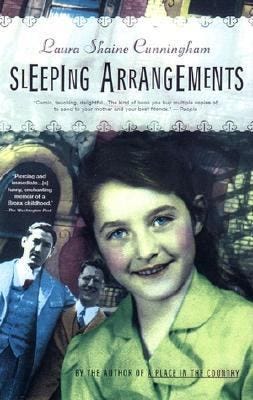

Let’s start with that second title first—Laura Shaine Cunningham’s Sleeping Arrangements. It turns out Cunningham was orphaned at age 10 by the death of her single mother, and sent to live with a pair of bachelor uncles.

Given this material, her book could have easily veered into the same maudlin or self-pitying trap that I describe above. Instead, Cunningham’s voice is funny, clear-sighted, gently ironic.

Her narrator is a real storyteller—funny, adventurous, and remarkably free of self-pity; notable given some of the darker territory she occasionally veers into. I picked the Cunningham example precisely because there’s so clearly an adult intelligence shaping this narrator’s voice.

So, how does the writer of a childhood memoir open the aperture of the narrator’s eye in a way that permits both the child and adult perspectives into the frame?

In Cunningham’s case, she does this by limiting the visual scope of what her narrator conveys. She describes her 10-year-old self’s physical world; we get to see things from her height, so to speak. But—and this is the crucial achievement—it is filtered through her current-day, mature perspective:

AnaMor Towers did not stand alone. The entire neighborhood was a cross section of ersatz bygone cultures. In the park, marble mermaids lounged, with rust running down their navels. Public buildings were supported by semi-nude figures, wearing New Deal chitons. Many of the apartment buildings were modern Towers of Babel, mixing details from Ancient Rome, Syria, Greece.

Here is the child’s limited field of vision, the attention to the kind of object that would interest the child—mermaids, blocky apartment buildings—but the syntax is that of an amused, historically-minded adult.

Above: This 1983 BBC documentary about George Orwell was named after a long (18,000 word!) autobiographical essay about his dismal early days at boarding school.

A similar technique shows up in another favorite of mine, George Orwell’s “Such, Such Were the Joys”. It’s impossible to forget the litany of humiliations that young George suffers at the hands of school administrators and older boys.

(The essay itself didn’t appear in book form until 1968—20 years after Orwell’s death, in part due to fear of British libel laws, while Orwell’s original literary executor called the piece "grossly exaggerated, badly written, and likely to harm Orwell's reputation.")

To my mind what makes this essay a masterpiece is the Orwellian narrator—that easy, clear-sighted way Orwell links his early torments to the larger social picture. (It’s easy to see how his school days led him to develop a strong sense of class consciousness).

Orwell accomplishes all of this by focusing on the child’s visual perceptions but not his limited understanding:

…One afternoon, as we were filing out from tea, Mrs Wilkes the Headmaster's wife, was sitting at the head of one of the tables, chatting with a lady of whom I knew nothing, except that she was on an afternoon's visit to the school. She was an intimidating, masculine-looking person wearing a riding-habit, or something that I took to be a riding-habit. I was just leaving the room when Mrs Wilkes called me back, as though to introduce me to the visitor. [my emphasis]

The focus on a strange and possibly frightening adult wearing a riding habit is the child’s. But both the description (“intimidating, masculine looking”) and the emphasis on the child’s possibly mistaken perception (“or something I took to be a riding-habit”) is that of the mature author.

In fact, this close attention to the mistaken apprehensions of childhood is a second technique that both Cunningham and Orwell use to create the sophisticated narrator of the childhood memoir.

In Cunningham’s case, she injects the adult’s greater sense of consciousness into her narrator in sections of the book that deal with matters far beyond the child’s limited ability to comprehend—an encounter with a pedophile, for example, or her mother’s impending death.

In this passage, she carefully layers the child’s misunderstanding of adult perceptions to great comic effect:

I have heard the family legend that Barb is a worthless “gold digger” who “hooked” Norm when Norm was a lonesome sailor…stationed in her southern city, so far from his own real home. What a gold digger would have seen in this near-retarded mechanic was questionable, but I accept on faith a cousin’s pronouncement that Barb “grabbed the brass ring.” Barb wears large brass hoops through her ears, which lends the legend credence.

Cunningham selects details that wink to the reader even as the child misunderstands or doesn’t comprehend exactly what she’s saying—as in the repetition of words the eight-year-old knows are probably bad (“gold-digger,” “hooked”) but doesn’t yet know.

Still confused? Try this writing exercise below.

Writing Exercise

1. Spend a moment centering yourself…and think of moments from when you were a child between, say, the ages of 6 to 10, and were confronted with something clearly beyond your years. It could be the first time you heard your parent’s fighting about something you didn’t quite understand; or maybe the first time you witnessed something violent you couldn’t process. It doesn’t have to be a sad or disturbing memory – maybe something funny, like witnessing an older teen’s first awkward attempts at dressing or acting grown-up. Just make it something outside the scope of an 6 or 8 or 10-year-old’s apprehension.

2. Now, free write for 10 minutes about one of these moments – don’t worry at this moment about the double consciousness or anything; just write.

3. Review what you’ve written. Look for those sentences or paragraphs in your work when your narrator is perceiving something she or he clearly doesn’t understand. Whose perspective have you conveyed them from? If it’s the child’s perspective, think about what it is that the child-character doesn’t understand.

Ask yourself: what would I explain to that younger self? If it looks like you’ve attempted to write from a more adult perspective, see if you’ve maintained that distance consistently throughout. Or is the voice a bit wobbly? – i.e. Are there places where you seem to be writing from your current, adult perspective and others where it seems like something a young child would say?

4. Pick one of the two narrators above – the Cunningham voice or the Orwell –and then rewrite your piece.

If you pick the Cunningham voice: remember to focus on what the child-character can actually see or perceive. Try your best to use your funny, witty adult self to actually describe the moment.

If you pick the Orwell voice: Focus on the incident and describe the child’s feelings or what she understands, but be sure to use your current day language to do so. (Extra points for Orwellian dry humor such as: “Night after night I prayed, with a fervor never previously attained in my prayers, 'Please God, do not let me wet my bed.”)

Did you try this writing exercise? Paste in a short sample in the comments below & I’ll guess which narrator you picked and leave some short feedback.

This fall I’m offering “Instant Clarity” Sessions

Join me for a highly focused, supportive, and transformative one-time session to gain clarity, create solutions that help you move past blocks, and leave with immediate actionable steps that will move you forward. These sessions are helpful if you are:

Feeling stuck or want another perspective on a specific project - literary or personal essay, article, Op-Ed, or other

Want clarity about any part of the publishing process, book proposal, book development, agent pitching, or other

Looking for advice or support about how to move forward with their writing career

Book a session by Sept 30th and get a 20% discount!

“I can't fully express how incredibly helpful and supportive today's meeting with you was for me. I feel like you really got who I am and in so doing, what my story is/could be and how I can express it in a film. Your suggestions feel spot on and provide me with a path that makes sense. You're really good at what you do!”

—Cynthia McKeown, August 2023 client and producer/director of the award-winning documentary, One in Eight: Janice's Journey.

A reader just pointed out that Jeannine Ouellete just wrote about the same subject -- brilliantly -- in the current issue of Assay magazine. Check out her essay here: https://www.assayjournal.com/jeannine-ouellette-that-little-voice-the-outsized-power-of-a-child-narrator-assay-92.html