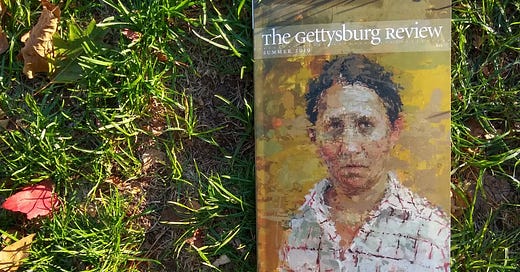

Last Wednesday, just as soon as my last newsletter went out, I read about Gettysburg College’s decision to shut down the vaunted Gettysburg Review, which will publish its last issue in December.

In a statement, President Bob Iuliano and Provost Jamila Bookwala blamed “changing demographic and enrollment realities across higher education,” continuing:

“…We must have a more intentional focus on the programs and activities that directly and significantly enhance student demand and the overall student experience.”

The news was surprising, to say the least. The Gettysburg Review is one of the best regarded lit journals in the country, often on various “top 10” lists. Over its 35 years it has published many greats, among them E.L. Doctorow,Rita Dove,

, James Tate—even , now one of Twitter/X’s most entertaining provocateurs.Oates pointed out that the Gettysburg Review is the reason most people have heard of the college in the first place:

Because the journal is so beloved—at least outside of Gettysburg College—it’s not surprising that Facebook and Twitter were flooded with calls to get the President and Provost to reverse the college’s decision. (Over at Lit Mag News,

has published a great roundup on ways to keep the heat on administrators).Still, as damaging as this news is to the larger literary community, I was curious to better understand the college’s rationale, as well as the larger—and difficult—environment for lit journals (esp those housed within higher ed) these days.

I wondered: why did the Gettysburg Review really close down? What does the news suggest for lit magazine and journals more broadly? And what if anything might help these journals to not just survive but thrive? (And note here—I’m talking about print-based lit journals, especially those based out of academia).

More about what those “changing demographic and enrollment realities” mean for lit journals

One thing that became quickly clear is that the college’s rationale is rooted in the current grim economic forecast for many institutions of higher ed.

As with pretty much every business in the world, the pandemic undercut operating revenues at Gettysburg; its been running significant deficits recently—a $6.7 million deficit in 2021 alone.

Those deficits are driven not just by pandemic-related revenue losses but the larger problem facing all of academia: decreasing enrollments. Or what Travis Kurowski, an associate professor at York University and an expert in lit mags, calls “the cliff of 18-year-olds.” (In 2022, the New York Times reported a nearly 5% decline in undergraduate enrollments from the previous year, a national trend that may continue for the foreseeable future).

In short, while one can question President Iuliano’s claim that the Gettysburg Review didn’t “directly and significantly enhance…the overall student experience” at Gettysburg College—and many have, given the 100+ student interns who’ve participated there over the years—the college faces the same bleak economic forecast that has pushed other higher ed institutions to make similar calls in recent years.

These are just some of the university-funded lit journals that have been shuttered or placed on hiatus since 2020: The Believer (University of Nevada), the Antioch Review (Antioch College), the Alaska Quarterly Review (the University of Alaska-Anchorage), and the Sycamore Review (Purdue University).

(UPDATED: The Alaska Quarterly Review continues to publish, though without support from the University of Alaska; meanwhile, McSweeney’s was able to buy back The Believer in 2022).

When I interviewed Travis Kurowski last week, he pointed out that literary magazines and journals have been associated with institutions of higher education for almost 100 years.

Often these journals were seen as prestige projects, aimed at enhancing the institutions beyond its walls—even as these journals were often subject to the vagaries of institutional budgets, priorities, and department allegiances, he explained.

But things have changed since those days.

“America doesn't really do as well as I would like to fund and support the arts. And that goes from the federal government down down to state governments. And then haven’t done as well, I think, to fund our education institution. So if we expect our higher education institutions to support these literary journals, I don't think that's going to be an ongoing thing because these institutions are getting less and less money as well from from funding sources,” Kurowski says.

In other words, when push comes to shove, and budgets tighten, lit journals, like the arts more generally, go on the chopping block. And with college and university budgets facing bleak prospects for the foreseeable future, the days of university-funded lit journals/prestige projects may be behind us.

Most lit journals haven’t adapted to the digital “literary economy”

In addition to the changing their reliance on shrinking university budgets, print-based literary journals have another major challenge: what Kurowski calls “the changing nature of the literary economy”—in other words, the way we’re all consuming media these days.

“You walk down any hallway, anywhere in your house, right? And we're just staring at their phones. We’re reading differently, we’re writing differently, we’re talking differently online. But our literary journals kind of look the same as they did 50 or 70 years ago,” he says.

By way of example, Kurowski points out that when he went to look at the Gettsyburg Review website to prep for our interview, he wasn’t able to click on any of the poems or short stories.

The problem actually goes beyond clickable websites, though. The very way we consume print magazines has profoundly shifted—something that publishing expert

has explored extensively.In her book The Business of Being a Writer, Friedman argues that the digital revolution has brought about the “disaggregation” of media. By which she means that journals are no longer consumed whole, cover-to-cover, but experienced in pieces, sometimes on platforms or in environments disaggregated, or pulled out, from their original format.

Whereas once a print copy of a magazine like The New Yorker might simply be read cover-to-cover, without expectation of engaging all that content on different platforms and in different ways, that’s simply not the case now.

Today, you can engage with the New Yorker through its website, podcast, app, and more—you can even engage with the magazine live, as in its New Yorker festivals. In other words, the magazine has unbound—disaggregated—itself.

Similarly, lit journals may have to learn to move beyond their print editions if they want to connect with new readers today. “You don't want to focus too much on the container but rather the content,” Kurowski says.

More than this, lit journals need to think about creating and fostering a creative community around them. Citing Friedman’s book, Kurowski says lit journals need to offer more than just stories, poems, and essays—they need to offer a space to experience and understand that writing.

“If a journal is not doing that, if they're not creating a brand, creating a community, creating an experience…it's going to be hard for them to fit into the 21st century, where content is essentially expected to be free,” he says.

Further reading…

I’ve barely scratched the surface on the changing landscape for literary journals. If you’re interested, I highly recommend Jane Friedman’s recent post, “Are Literary Journals in Trouble?” here.

In addition to the need to disaggregate content, Friedman also (rightly) points out that for lit journals to survive and thrive, they need to rethink a model based on scarcity and gatekeeping.

“Instead of clinging to the scarcity model, they should create more opportunities for publication and engagement, with themselves as the leaders and moderators in the community. When the number of visits to a publication’s submission guidelines page is greater than that of any of its content—but there’s no interaction with those writers, and in fact writers are simply asked to pony up for a subscription—that sets up a dynamic in which the people who should value you come to either hate you or ignore you. And that is exactly what is happening,” Friedman writes.

A longer version of Friedman’s essay can be found in the anthology The Little Magazine in Contemporary America, coedited by Ian Morris and Joanne Diaz.

I also highly recommend Literary Publishing in the Twenty-First Century, coedited by Travis Kurowski, Wayne Miller, and Kevin Prufer.

And stay tuned for the full interview with Travis Kurowski on the demise of the Gettysburg Review and the future of lit journals, to be released later this year on Season 3 of The Book I Had to Write podcast.

CORRECTION: The Alaska Quarterly Review still publishes between one and two issues a year, though without support from the University of Alaska.

Tell Me What You Think!

I really love hearing from readers of this newsletter. If you have something interesting—or just kind—to say, please feel free to leave a comment below!

The whole submission process has changed too! Instead of photocopying (or typing out!) a piece, finding an envelope, stamp, and then another envelope and stamp to serve as a SASE and then walking the whole thing to the post office and waiting for an acceptance or more likely rejection by mail we have. . Submittable, a platform I have not yet mastered. Not to mention the submission FEE that is no doubt necessary to online survival.

I love this newsletter of yours. I didn't know about the end of those magazines. Most were too high a bar for me. I hate that the Alaska Quarterly Review is gone, what a great place that was. Back in the day being published in a magazine made of paper used to be a thrill., still is. But nowadays, being published online has taken its place, being available to anyone with a computer or a phone, and it feels pretty nice too. And a place like Air/Light not only publishes interesting stuff, but it is also quite beautiful, and the illustrations would be prohibitively expensive to do in an actual hold in your hands magazine.